Year of the Dragon

Celebrate the 2024 Lunar New Year, Year of the Dragon, with highlights from the collection

The Lunar New Year 2024 ushers in the Year of the Dragon, which is celebrated in many Asian countries such as China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia. According to the foundational legend, the Jade Emperor challenged a group of animals, promising that whoever crossed a rushing river first would have a calendar year named in their honor. Coming in fifth place, right after the rabbit, was the mighty dragon. The Year of the Dragon occurs once every twelve years, and those born under its sign are said to inherit the mythical creature’s auspicious traits. Power, strength, confidence, and ambition are some of the traits most commonly ascribed to the traditional Chinese dragon.

We invite you to take a dragon-inspired tour through the Museum’s collections and celebrate the Lunar New Year. From scaly lizards to mummified cave-snakes, the legacy of this majestic and enigmatic creature continues to be reflected in natural history to this day.

An Introduction to Dragons

The dragon that is a part of the Zodiac is very different from the type of dragon most commonly recalled by Western audiences. In the European tradition, the dragon is a malevolent beast, often intent on protecting a hoard of riches or bringing destruction to those foolish enough to challenge its supremacy. It is often depicted as an armored, serpent-like creature with leathery wings and a coiled tail. Western dragons also characteristically breathe fire. The European dragon’s persistent malevolent connotations can be directly attributed to the influence of early Christianity, where the dragon and its serpentine relations were often regarded as stand-ins for the devil.

Conversely, Chinese dragons, or long, were heralded as bringers of good fortune through their association with rain and water. Asiatic dragons have long been bestowed with power over bodies and the divine ability to bring rain. Rain-bringing was an all-important quality for the primarily agricultural society of ancient China, a time period during which the earliest recorded depictions of a dragon–dating as far back as the 5th millennium BCE were unearthed. This auspicious association with potent good fortune has made the dragon figure omnipresent throughout China and many neighboring Asian countries. The dragon’s authoritative supernatural powers have also lent itself to being used to symbolize imperial Chinese authority. Ancient Chinese emperors were regarded as descendants of dragons and were said to be able to commune with the mythical creatures to obtain earthly wisdom.

NHM houses millions of specimens actively used for research every day. Elements, characteristics, and depictions of this fantastical creature are present throughout the collections. We invite you to explore the images below to see how the dragon—a persistent symbol of power, mythology, and enchantment—has manifested itself in the Museum collections.

Dragons at the Museum

How to Build Your Dragon

Chinese dragons differ stylistically from European dragons. Although Chinese dragons have the ability to fly, they do not have wings. They traditionally do not breathe fire but do have the power to shapeshift into different animals or even people. A Chinese dragon constituted a type of composite being. Traditionally, a Chinese dragon was regarded as being composed of the following traits, although particulars vary by region and ethnic group: the head of a camel (or horse), the antlers of a stag, the eyes of a demon (or rabbit), the neck of a snake, the belly of a clam, the scales of a carp, the claws of an eagle, the paws of a tiger, and the ears of a cow. Scroll through the photos below to imagine a dragon made up of these different elements from specimens on display at the Museum and in the collections.

Justin Ramos

Chinese dragons are typically depicted with antlers. The antlers of a North American mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), on display in the North American Mammal Hall, would make a fine addition to any dragon.

Justin Ramos

Chinese dragons are depicted as having a head like that of a horse or camel. Oxydactylus campestris is an extinct, giraffe-like camel that fed on trees and shrubs in the fertile forests of North America during the Early Miocene period (about 18 million years ago). This specimen is on display in the Museum's Age of Mammals exhibition hall.

Justin Ramos

The piercing, red-orange eyes of a rabbit seem befitting of a wise dragon. This black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus) is on display in the Museum's Nature Lab.

Justin Ramos

Dragons and serpents have long shared a history together, especially in the Western imagination. Traditionally, a Chinese dragon was believed to have the scaly neck of a snake. Pictured here are the scales on a Western Pacific rattlesnake (Crotalus oreganus), on display in the Museum's Nature Lab.

Dr. Todd Clardy

The mighty dragon and the common goldfish (Carassius auratus) share one thing in common—their scales.

Justin Ramos

Chinese dragons are depicted as having the sharp claws of an eagle. These claws belong to the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), a large predatory bird that can still be found in some part of Los Angeles County. This eagle is on view in the Museum's Nature Lab.

Dr. Jann Vendetti

Although clams, like this Pismo Clam (Tivela stultorum) from San Luis Obispo County, do not really have bellies, a dragon's underside is said to be as rigid as a clamshell.

Justin Ramos

In Chinese mythology, a dragon's claws are embedded into the paws of a tiger. This Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) is on display in the Museum's Age of Mammals exhibition hall.

Justin Ramos

Chinese dragons are usually depicted with cow-like ears. This breed of corriente cow (Bos taurus) is on display in the Museum's Becoming Los Angeles exhibition. Try and spot the ears (usually near the base of the antlers) the next time you see a depiction of a Chinese dragon.

1 of 1

Chinese dragons are typically depicted with antlers. The antlers of a North American mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), on display in the North American Mammal Hall, would make a fine addition to any dragon.

Justin Ramos

Chinese dragons are depicted as having a head like that of a horse or camel. Oxydactylus campestris is an extinct, giraffe-like camel that fed on trees and shrubs in the fertile forests of North America during the Early Miocene period (about 18 million years ago). This specimen is on display in the Museum's Age of Mammals exhibition hall.

Justin Ramos

The piercing, red-orange eyes of a rabbit seem befitting of a wise dragon. This black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus) is on display in the Museum's Nature Lab.

Justin Ramos

Dragons and serpents have long shared a history together, especially in the Western imagination. Traditionally, a Chinese dragon was believed to have the scaly neck of a snake. Pictured here are the scales on a Western Pacific rattlesnake (Crotalus oreganus), on display in the Museum's Nature Lab.

Justin Ramos

The mighty dragon and the common goldfish (Carassius auratus) share one thing in common—their scales.

Dr. Todd Clardy

Chinese dragons are depicted as having the sharp claws of an eagle. These claws belong to the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), a large predatory bird that can still be found in some part of Los Angeles County. This eagle is on view in the Museum's Nature Lab.

Justin Ramos

Although clams, like this Pismo Clam (Tivela stultorum) from San Luis Obispo County, do not really have bellies, a dragon's underside is said to be as rigid as a clamshell.

Dr. Jann Vendetti

In Chinese mythology, a dragon's claws are embedded into the paws of a tiger. This Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) is on display in the Museum's Age of Mammals exhibition hall.

Justin Ramos

Chinese dragons are usually depicted with cow-like ears. This breed of corriente cow (Bos taurus) is on display in the Museum's Becoming Los Angeles exhibition. Try and spot the ears (usually near the base of the antlers) the next time you see a depiction of a Chinese dragon.

Justin Ramos

Dragons in L.A.

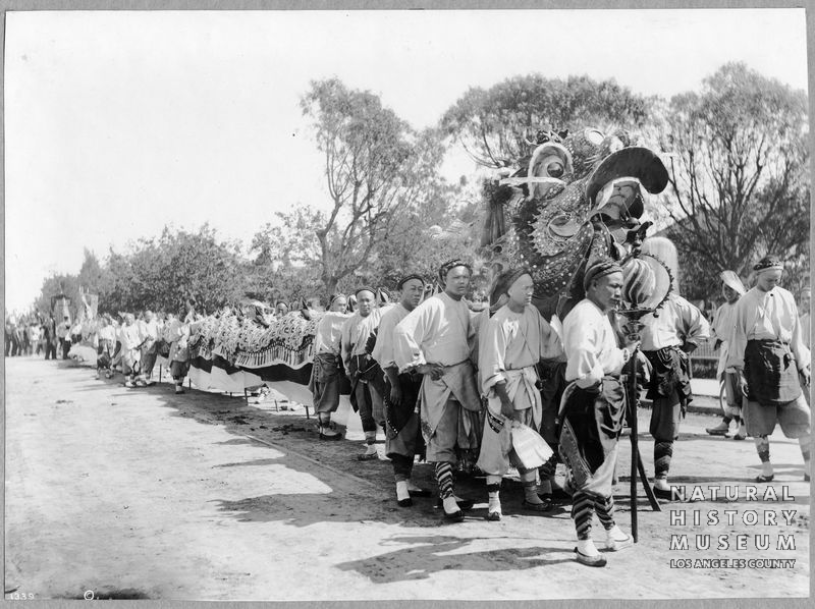

This photograph, taken in Los Angeles's Chinatown in the 1930s, shows Chinese dragon dancers readying themselves for a performance. The visually dynamic dragon dance traces its roots to Han dynasty China (206 BCE- 220CE) and was initially danced to call forth rain from the powerful dragon. Today, dragon dances are still performed as a staple part of traditional Chinese festivals in an effort to bring forth good fortune and to cast away evil influences.

This photo, dating from around 1900, shows the multitude of dancers that make up the head and the body of the dragon. At the head of the dragon, a man holds a staff upon which rests an orb. This ball represents the mystical Pearl of Wisdom, and as the dancer with the pearl moves in a choreographed pattern, so follows undulating body of the dragon. The dragon dance represents the dragon's eternal pursuit of wisdom and knowledge. This dazzling dance is often accompanied by the rhythmic beating of cymbals, drums, and gongs.

A Reptilian Lineage

With their scaly bellies, forward-facing eyes, sharp claws, and long tails, dragons easily share many attributes with their reptilian antecedents. Scroll through the photos below to see how dragon-like some reptiles can appear!

Justin Ramos

This mummified Trans-Pecos rat snake had been preserved in a cave by the dry heat of the Chihuahuan deserts of New Mexico. Although remaining mostly intact, the snake was last alive during the late Pleistocene age, about 126,000 to 11,700 years ago. According to Chinese mythology, the dragon’s neck is that of a snake.

Justin Ramos

This mummified, late Plesitocene-head of a western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) was found in the same cave as the previous snake. Chinese dragons are often depicted bearing their powerful fangs, a feature still sharply apparent on this millennia-old rattlesnake.

Justin Ramos

The gliding lizard belongs to the genus Draco, meaning "dragon" in Latin. As the name suggests, gliding lizards are able to glide distances of up to 200 feet by extending a thin, rib-supported skin membrane which extends from their fore to hind legs. Gliding lizards live in the tropical rain forests of India and Southeast Asia, residing primarily amongst the treetops where they use their gliding powers to skim from tree to tree.

Justin Ramos

Despite its mythical namesake, the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) is no less impressive in its size and capabilities. The largest of all lizard species, a komodo dragon can grow up to 10 feet long and weigh as much as 150 pounds. Here, the giant lizard is preserved in a special large tank of alcohol, its body kept intact to enable researchers and scientists from around the world to study the science behind this unique species.

Justin Ramos

The sungazer lizard, due to its striking dragon-like appearance, belongs to the genus Smaug, so named after the dragon in J.R.R. Tolkien’s "The Hobbit." Smaug giganteus is endemic to the highlands of South Africa and spends most of its life living in burrows. Completely covered in scaly armor and spikes, Smaug giganteus subsists mostly on insects. Its prominent occipital spikes have served as direct inspiration for the design of the dragons on "Game of Thrones." Sungazer lizard populations are threatened due to its desirability in the pet trade, its use in traditional medicine, and an increased loss of its native grassland habitat.

Justin Ramos

Though small, this juvenile Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) displays the traits which have earned it an abiding close association with dragons. Throughout history, crocodiles have often been equated with dragons due to their large size and ferocious appearance.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County- Living Collections Department

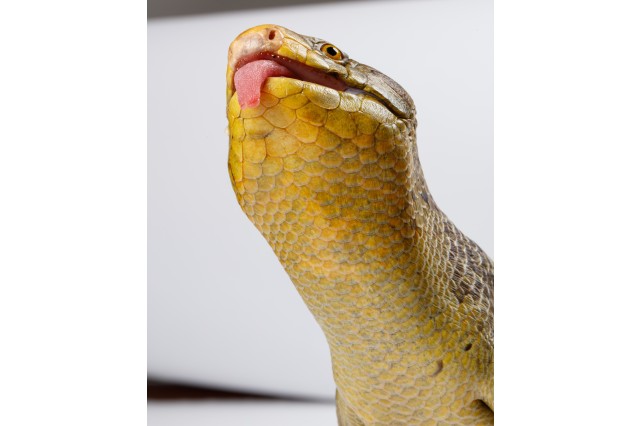

Skinks are one of the most diverse and common groups of lizards with a global distribution. Tallulah, the Solomon Island skink (Corucia zebrata), is one of the stars of the Museum’s Living Collections. With its scaly underbelly and fleshy tongue, the Solomon Islands skink is an arboreal lizard that subsists primarily on insects.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County- Living Collections Department

Chinese and European dragons are often depicted with their tongues stuck out. Rabbit, the Museum’s Colombian red-tailed boa (Boa constrictor imperator), does her best dragon impression. Although they do not breathe fire, all snakes (including Rabbit), use their forked tongue to sense and interpret odor molecules in the air, allowing them to track prey.

1 of 1

This mummified Trans-Pecos rat snake had been preserved in a cave by the dry heat of the Chihuahuan deserts of New Mexico. Although remaining mostly intact, the snake was last alive during the late Pleistocene age, about 126,000 to 11,700 years ago. According to Chinese mythology, the dragon’s neck is that of a snake.

Justin Ramos

This mummified, late Plesitocene-head of a western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) was found in the same cave as the previous snake. Chinese dragons are often depicted bearing their powerful fangs, a feature still sharply apparent on this millennia-old rattlesnake.

Justin Ramos

The gliding lizard belongs to the genus Draco, meaning "dragon" in Latin. As the name suggests, gliding lizards are able to glide distances of up to 200 feet by extending a thin, rib-supported skin membrane which extends from their fore to hind legs. Gliding lizards live in the tropical rain forests of India and Southeast Asia, residing primarily amongst the treetops where they use their gliding powers to skim from tree to tree.

Justin Ramos

Despite its mythical namesake, the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) is no less impressive in its size and capabilities. The largest of all lizard species, a komodo dragon can grow up to 10 feet long and weigh as much as 150 pounds. Here, the giant lizard is preserved in a special large tank of alcohol, its body kept intact to enable researchers and scientists from around the world to study the science behind this unique species.

Justin Ramos

The sungazer lizard, due to its striking dragon-like appearance, belongs to the genus Smaug, so named after the dragon in J.R.R. Tolkien’s "The Hobbit." Smaug giganteus is endemic to the highlands of South Africa and spends most of its life living in burrows. Completely covered in scaly armor and spikes, Smaug giganteus subsists mostly on insects. Its prominent occipital spikes have served as direct inspiration for the design of the dragons on "Game of Thrones." Sungazer lizard populations are threatened due to its desirability in the pet trade, its use in traditional medicine, and an increased loss of its native grassland habitat.

Justin Ramos

Though small, this juvenile Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) displays the traits which have earned it an abiding close association with dragons. Throughout history, crocodiles have often been equated with dragons due to their large size and ferocious appearance.

Justin Ramos

Skinks are one of the most diverse and common groups of lizards with a global distribution. Tallulah, the Solomon Island skink (Corucia zebrata), is one of the stars of the Museum’s Living Collections. With its scaly underbelly and fleshy tongue, the Solomon Islands skink is an arboreal lizard that subsists primarily on insects.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County- Living Collections Department

Chinese and European dragons are often depicted with their tongues stuck out. Rabbit, the Museum’s Colombian red-tailed boa (Boa constrictor imperator), does her best dragon impression. Although they do not breathe fire, all snakes (including Rabbit), use their forked tongue to sense and interpret odor molecules in the air, allowing them to track prey.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County- Living Collections Department

Extinct Reptiles

No list of dragon-like animals would be complete without the mention of dinosaurs (as well as ichthyosaurs and pterosaurs). Equally as captivating and enigmatic as dragons, but wholly based in real scientific evidence, dinosaurs and other extinct reptiles have undoubtedly served as inspiration for their mythic counterparts. The existence of “dragon bones” was common knowledge in ancient and historic China. This fossil material was believed to have potent curative properties, and had been extensively used in traditional Chinese medicine. The “dragon bone” designation was a catch-all term, being used to describe fossil material that has been proven to be mostly from extinct mammals. However, given the amount of dinosaur fossil material that exists in China and the historic proliferation of using fossil material in dragon bone medicine, it stands to reason that some dinosaur bones were used in this manner. As recent as 2007, scientists discovered that villagers in Central China were using locally found dinosaur material in traditional medicine applications.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Dinosaur Institute

Pterosaurs are a group of extinct flying reptiles that existed for most of the “Age of Reptiles," or the Mesozoic Era. They hold the distinction of being the earliest vertebrates to have developed the power of flight. Pterosaur wings were made up of a skin membrane that extended from their shoulder to their ankle, supported by an elongated digit. Pictured is a cast of Rhamphorhynchus, a fish-loving pterosaur that lived during the Jurassic Period and was excavated in Germany. Although both European and Chinese dragons have the ability to fly like a pterosaur, the Chinese dragon does so without wings.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Dinosaur Institute

This cast of a fossilized pterosaur, Campylognathus, clearly shows the long, finger-like digits onto which their fleshy membrane was affixed. Pterosaurs also had tails of varying lengths to act as flight stabilizers.

This assemblage on bones, including a Late Jurassic partial pterosaur humerus, demonstrate both the delicate yet robust morphology of pterosaur bones which enable flight. Much like the bones of birds, pterosaur bones are mostly hollow, allowing for a greater strength-to-weight ratio. This also makes the articulated fossils of pterosaurs a greater challenge to find.

This fossilized skull of a Cymbospondylus belongs to a group of marine reptiles known as ichthyosaurs. Cymbospondylus lived in the Middle Triassic, about 247-237 million years ago and are now found in modern-day North America and Western Europe. Although not a dinosaur, ichthyosoaurs are evocative of Chinese dragons because of their association with bodies of water.

1 of 1

Pterosaurs are a group of extinct flying reptiles that existed for most of the “Age of Reptiles," or the Mesozoic Era. They hold the distinction of being the earliest vertebrates to have developed the power of flight. Pterosaur wings were made up of a skin membrane that extended from their shoulder to their ankle, supported by an elongated digit. Pictured is a cast of Rhamphorhynchus, a fish-loving pterosaur that lived during the Jurassic Period and was excavated in Germany. Although both European and Chinese dragons have the ability to fly like a pterosaur, the Chinese dragon does so without wings.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Dinosaur Institute

This cast of a fossilized pterosaur, Campylognathus, clearly shows the long, finger-like digits onto which their fleshy membrane was affixed. Pterosaurs also had tails of varying lengths to act as flight stabilizers.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Dinosaur Institute

This assemblage on bones, including a Late Jurassic partial pterosaur humerus, demonstrate both the delicate yet robust morphology of pterosaur bones which enable flight. Much like the bones of birds, pterosaur bones are mostly hollow, allowing for a greater strength-to-weight ratio. This also makes the articulated fossils of pterosaurs a greater challenge to find.

This fossilized skull of a Cymbospondylus belongs to a group of marine reptiles known as ichthyosaurs. Cymbospondylus lived in the Middle Triassic, about 247-237 million years ago and are now found in modern-day North America and Western Europe. Although not a dinosaur, ichthyosoaurs are evocative of Chinese dragons because of their association with bodies of water.

Small but Dragon-y

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Invertebrate Paleontology collection

No list of dragon-like creatures would be complete without mention of dragonflies. This is a compression fossil of a dragonfly that lived in Germany during the Jurassic Period. Around 155 million years ago, Germany consisted of many islands separated by anoxic (low in oxygen) lagoons which were uninhabitable for many organisms. With a lack of scavenging organisms and strong currents, a fallen dragonfly would have been covered by the soft muds at the bottom of the lagoon. This mud burial preserved the fragile body of the dragonfly which was later flattened by the pressure of the overlying sediment.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Mammalogy Department

All bats, in the order Chiroptera, have wings that are skin membranes over hand bones, similar to dragons. In fact, European-style dragons are often depicted walking on their thumbs the same way bats do.

Justin Ramos

Despite having scales and sharp claws like a reptilian dragon, a pangolin is, in fact, a mammal belonging to the order Pholidota. Pangolins are found in the forests and grasslands of Africa and Asia, and are listed by the World Wildlife Foundation as vulnerable to critically endangered. They primarily subsist on ants and other small insects.

Dr. Todd Clardy

This fearsome looking fish is called a Pacific blackdragon, or black sea dragon (Idiacanthus antrostomus). Although it has lost most of its color since being preserved, in life the black sea dragon has special pigment cells that absorb most of the ambient light, making it nearly imperceptible to surrounding prey.

Justin Ramos

Although it may look like a normal squirrel at first glance, the underside of this scaly-tailed squirrel (which is technically not even a squirrel) reveals some of its dragon-like characteristics. Scaly-tailed squirrels, or anomalures, use the scales at the base of the underside of their tails to grip when they are climbing up trees, because, although they don’t fly, they do glide!

1 of 1

No list of dragon-like creatures would be complete without mention of dragonflies. This is a compression fossil of a dragonfly that lived in Germany during the Jurassic Period. Around 155 million years ago, Germany consisted of many islands separated by anoxic (low in oxygen) lagoons which were uninhabitable for many organisms. With a lack of scavenging organisms and strong currents, a fallen dragonfly would have been covered by the soft muds at the bottom of the lagoon. This mud burial preserved the fragile body of the dragonfly which was later flattened by the pressure of the overlying sediment.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Invertebrate Paleontology collection

All bats, in the order Chiroptera, have wings that are skin membranes over hand bones, similar to dragons. In fact, European-style dragons are often depicted walking on their thumbs the same way bats do.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Mammalogy Department

Despite having scales and sharp claws like a reptilian dragon, a pangolin is, in fact, a mammal belonging to the order Pholidota. Pangolins are found in the forests and grasslands of Africa and Asia, and are listed by the World Wildlife Foundation as vulnerable to critically endangered. They primarily subsist on ants and other small insects.

Justin Ramos

This fearsome looking fish is called a Pacific blackdragon, or black sea dragon (Idiacanthus antrostomus). Although it has lost most of its color since being preserved, in life the black sea dragon has special pigment cells that absorb most of the ambient light, making it nearly imperceptible to surrounding prey.

Dr. Todd Clardy

Although it may look like a normal squirrel at first glance, the underside of this scaly-tailed squirrel (which is technically not even a squirrel) reveals some of its dragon-like characteristics. Scaly-tailed squirrels, or anomalures, use the scales at the base of the underside of their tails to grip when they are climbing up trees, because, although they don’t fly, they do glide!

Justin Ramos