We Found Bats Living at La Brea Tar Pits!

We’ve recently discovered that bats are still flying over the Tar Pits on a regular basis!

Published October 9, 2014

If you’ve ever been to La Brea Tar Pits you might have wondered if bats were around during the last Ice Age when saber-toothed cats (Smilodon fatalis), Columbian mammoths (Mammuthus columbi), and dire wolves (Canis dirus) roamed the land that is now our city. Well, we’re happy to tell you that the answer is yes, and we’ve recently discovered that bats are still flying over the Tar Pits on a regular basis!

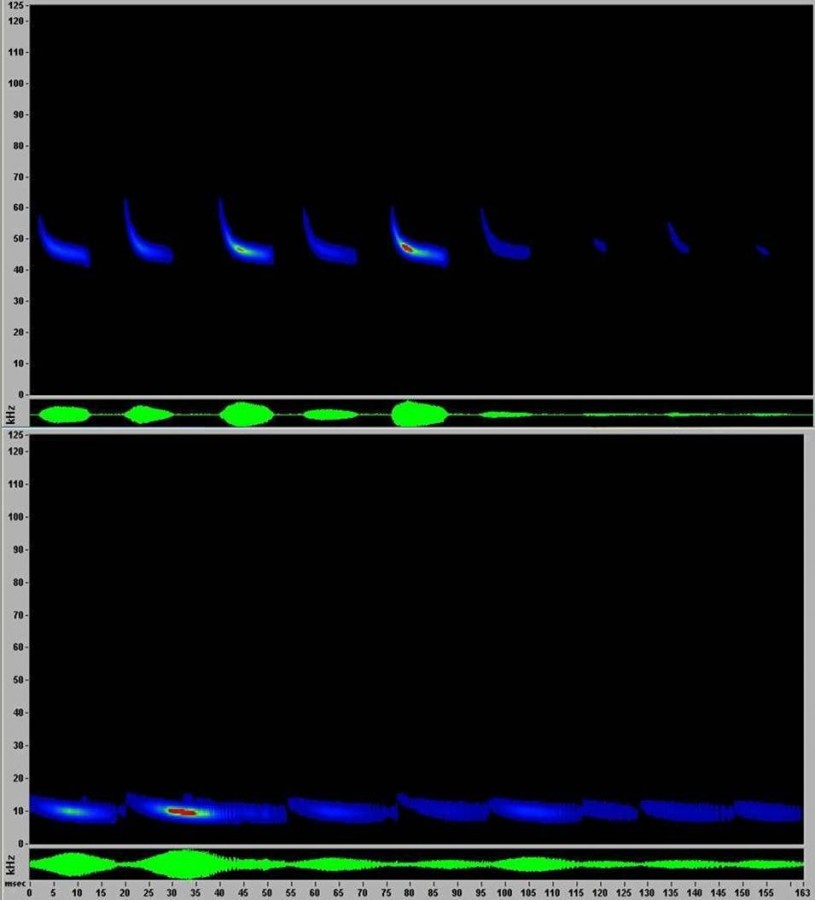

But how do we know that bats are still living in the Miracle Mile? It’s all thanks to bat detectors. Bat detectors are devices myself and other scientists use to record the ultrasonic calls—remember echolocation from biology class—that bats use to communicate, hunt, and find their way around in the dark. I then use special computer programs that turn the calls into sonograms so I can visualize the call. Because each bat species’ call is distinct, I can then tell which bats have been flying near my detector.

Here are some sonograms of bats I detected at the L.A. Zoo: Pictured top is the canyon bat (Parastrellus hesperus), and below is the Western mastiff (Eumops perotis).

In early July, I set up a bat detector along the shore of the big lake at the Tar Pits. I knew the site seemed like great bat habitat because it has a body of water which helps to support insects (a.k.a. bat food), and there are lots of trees for bats to roost in. However, this still felt like a big gamble to me. There are no bat specimens from the Tar Pits or Hancock Park in the museum’s Mammalogy collection, and this is really expensive gear.

But after communicating with our paleontologists that work at the George C. Page Museum, I learned that bats did in fact use the area during the last Ice Age. Research conducted by Bill Akersten (former curator at the Page Museum) in the late 1970s found that unlike the hundreds of dire wolves that have been found at the Tar Pits, bat fossils were rarely recovered because they are fragile and small. Only two bat species have been confirmed at the Tar Pits, the pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus), and the hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus). Although the environment has gone through dramatic changes since then, I find it remarkable that these two species still live in our region. But how many bats call the Tar Pits home today?

Just two months after I installed our bat detector in July 2014, we have discovered four species of bats at the Tar Pits! The detector has recorded the following species big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus), canyon bat (Parastrellus hesperus), Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), and Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis). I don’t find it that surprising that we didn’t record the pallid or hoary bat as these species are more sensitive to urbanization. However, I’m hopeful that the gardens we’ve been planting at both the Tar Pits, and the Nature Gardens at NHM will provide good habitat for more species of bats.

Case in point—in September 2013, the museum’s Mammalogy Collections Manager, Jim Dines, and I set up a bat detector in the museum’s Nature Gardens. Over the last year, we’ve recorded four species of bats in the gardens. If you want to hear that story, you’ll have to wait until later this month during National Bat Week! So turn your echolocation on and stay tuned, and in the meantime take a moment to think about the bats that fly over the Tar Pits and your neighborhood nightly, and what life would have been like for bats, birds, and bees in the Ice Age!