Minerals with Lead-busting Superpowers

Our scientists are harnessing the properties of a mineral to encapsulate dangerous lead in soil in South L.A. backyards, demonstrating how NHM discoveries coupled with community partners can power environmental change.

Published March 2, 2023

Lead, a heavy metal, has taken up residence in East Los Angeles neighborhoods and stayed there for decades. A toxic byproduct from a battery recycling plant, lead contaminates the soil in yards where thousands of children play. Recently, a powerful coalition of artists, scientists, and community partners have committed to the work of addressing this environmental scourge. Their instrument? The mineral, zeolite.

NHMLAC’s co-created initiative Prospering Backyards melds art, science, and community with the mission to heal the lead-contaminated land in areas including Boyle Heights, Vernon, Commerce, Maywood, Huntington Park, and Bell while bolstering the health of the soil and the environment. Lead can easily be accumulated into the body by absorption through the skin, drinking water, or breathing contaminated dust. The effects of lead exposure can include: impaired development, reduced intelligence, loss of short-term memory, learning disabilities, and coordination problems, kidney failure, and increased risk for the development of heart and circulatory system diseases.

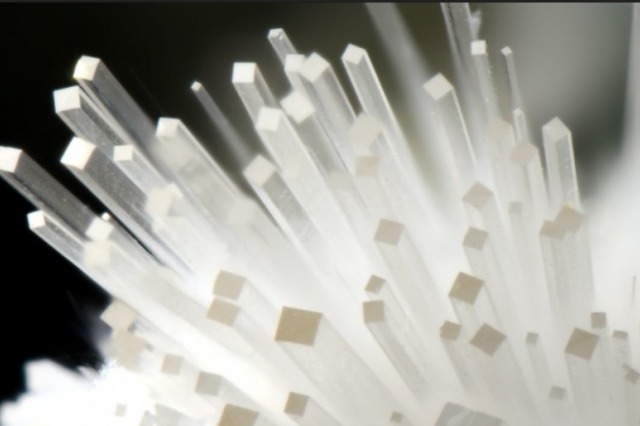

Aaron Celestian, NHM’s Curator of Mineral Sciences, discovered that zeolite is capable of targeting and essentially vanquishing this environmental bad actor by entombing it in place. “Zeolite means ‘boiling rock’” says Celestian. “You heat it up, you put it on the stove, it’ll start oozing out water. When it cools off, it reabsorbs that water into the crystals. So it’s kind of like a sponge.” There are 120 different types of zeolite and this capacity to soak up liquid makes it a popular commercial product. It’s in the artificial turf on football or soccer fields (helps to neutralize the stinky odor) and is used in many cat litters because it naturally clumps.

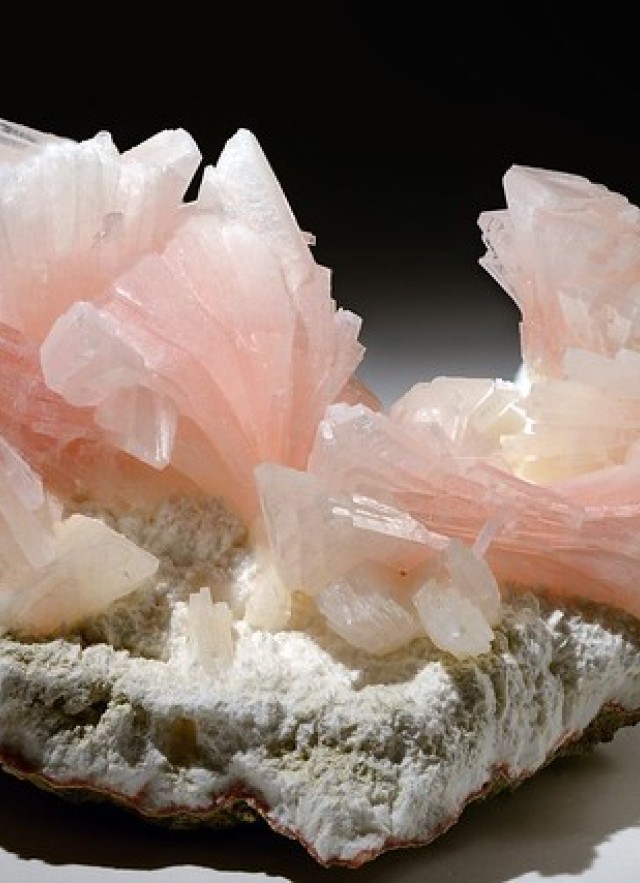

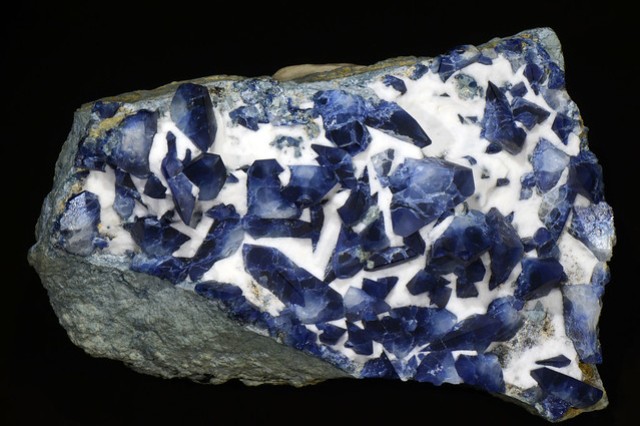

Benitoite Gem from New Idria district, San Benito, California. Part of NHMLAC's Gem and Mineral Collection.

Benitoite Gem mine, New Idria district, San Benito, California. Part of the Gem and Mineral Hall Collection.

Mesolite. Pashan Hills, Maharashtra, India. From NHMLAC's Gem and Mineral Collection.

1 of 1

Benitoite Gem from New Idria district, San Benito, California. Part of NHMLAC's Gem and Mineral Collection.

Benitoite Gem mine, New Idria district, San Benito, California. Part of the Gem and Mineral Hall Collection.

Mesolite. Pashan Hills, Maharashtra, India. From NHMLAC's Gem and Mineral Collection.

Celestian discovered that a particular zeolite—clinoptilolite—is perfectly matched to slurp up lead and entomb it in the ground for decades. “It’s got the right-sized hole for the atom of lead to go into, and when it goes in, the hole behind it closes down, it locks it into place.” If the lead is stuck inside the zeolite and can't come back out, it's no longer able to participate in any kind of biological reactions and is therefore completely benign.” Conveniently, the mineral is organically found in California. Through a partnership with a mining company in the Mojave Desert, Celestian was able to secure a sufficient amount of the white powder for Prospering Backyards.

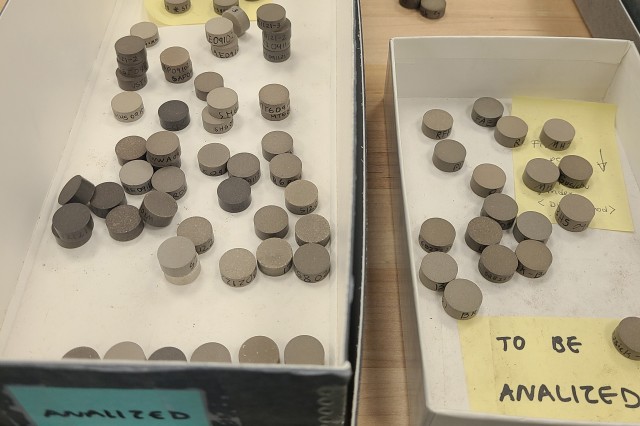

This project is an exciting, evolving experiment seeking to answer several fundamental scientific research questions. What, for instance, are the molecular mechanisms at work when zeolite is installed? How are organic processes (the growth of microorganisms, for instance) affected when zeolite penetrates deep in natural soils? The next steps in the project’s timeline include continuing the installation of zeolite in backyards and collecting soil from homes on a monthly schedule through February 2024; processing the soil samples to test for lead, as well as environmental DNA, through February 2024; and analyzing the data through March 2024. The project wraps up in Spring 2024.

A Home Visit

On a recent February afternoon, Celestian and two students working in the Mineral Science Lab head out to meet Martha Recio and her family in their Highland Park home, where they have lived for seven years. Based on soil samples they’d collected earlier (just a couple of spoonfuls) the scientists learned the lead levels were very high, at 440 parts per million.

“We were surprised when they came back with the results…I was interested because I heard about the battery company, which triggered me to want to know more,” Recio says that day in her front yard surrounded by her husband, kids and parents. “Thinking about all the stuff we have grown here and our kids have been here since day one. They used to come here and play. In the summer we’d run the water. So we were worried. They have been tested though and have been fine. We avoid spending time in the front yard. It’s great that there is a group of people willing to help fix it.”

After Celestian and two students—Charlie Nichols, studying geology at Santa Monica College, and Alexia Rojas, a PhD student in geology at USC—arrive in the yard, they pick a patch of dirt where there isn’t foot traffic to take baseline lead levels. Using an auger and wearing gloves (so they don’t deposit their DNA in the sample), Celestian lifts a teaspoon of dirt and passes it to one of his students who places it in a vial, then a plastic bag in an envelope which records the particulars of time, date and location. They leave signs and rods with flags to note the testing site for subsequent visits. These samples are put on ice and destined for the Mineral Science Lab’s freezer. They are also taking baseline DNA samples to test the health of the soil microbiome; later they will grow vegetables in the raised garden beds, add compost and mulch, and analyze the plants and soil to test the extent of the mineral’s lead-busting prowess.

Once the sampling is done, volunteers hoist heavy bags of zeolite and the group of scientists and community members take handfuls and spread a layer of the pulverized mineral across the yard until it's blanketed white. “It looks like snow on the ground. That’s the look we’re going for,” says Celestian. Once applied, the zeolite works its way into the ground where it will absorb the lead very rapidly, in about 30 seconds.

Soil Time

The science behind this mineral has undeniable gravitas, but the whole enterprise is also grounded in art. Maru García, a Mexican, L.A.-based artist and chemist, and the project lead for Prospering Backyards, launched Soil Time workshops as part of Self-Help Graphics & Art, the community hub for the project. The free public bilingual workshops on soil health include studies of living organisms (bacteria, fungi, centipedes, and other creatures) living in the dirt beneath our feet. The educational and art-related activities are helping participants identify the importance of soil health as a source of food, carbon sequestration (the process of removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere with the goal of reducing global climate change), and a strategy for building resilient and sustainable communities.

García sees this as an opportunity for participants to be agents of transformation. “I believe we have an immense capacity to not just be spectators but to see ourselves as regenerators,” says Garcia. A message on their website declares this intention: “Soil is life! We want our children to be able to play safely in our own backyards. We want to be able to grow our own food.”

Image by Sam Tayag

Maru Garcia taking soil samples from an East L.A. home.

By Maru Garcia

Applying zeolites to a raised planter bed.

Image by Sam Tayag

Soil samples processed for lead testing in Mineralogy Lab.

1 of 1

Maru Garcia taking soil samples from an East L.A. home.

Image by Sam Tayag

Applying zeolites to a raised planter bed.

By Maru Garcia

Soil samples processed for lead testing in Mineralogy Lab.

Image by Sam Tayag

Marvella Muro, the Director of Artistic Programs and Education at Self Help Graphics & Arts, said the project is important to facilitate lead stabilization for families whose properties are not on a government cleanup priority list. “There are so many homes to be remediated, so this is a way for us to be able to help those who don’t qualify.” Each of the community members will be given a DIY soil healing kit including gloves, bags, and cleaner, which they’ll use to take monthly samples. The yearlong project will help 15 households, building a cohort of yearlong community scientists. That will, in turn, have an impact on science at large; these volunteers will be helping to generate new knowledge about zeolite’s lead-encapsulating potential.

Self Help Graphics & Arts is part of the regional arts initiative, Pacific Standard Time, scheduled to open in 2024.

Many of the community scientists in the Prospering backyards team are also active in grassroots neighborhood efforts to take action for environmental justice in East Los Angeles. Organizations such as East Yards Communities for Environmental Justice and Visión City Terrace have deep-rooted, strong networks of dedicated community members whose work spans from policy advocacy to connecting people to vital health and safety resources. The Prospering backyards team hopes this research will support long-standing community work for a safe and healthy East L.A.

Towards the end of the visit to her Highland Park home, Recio talked enthusiastically about participating in the data-gathering experiment in her front yard. “It's amazing to have the help, especially to have people who are experts doing this with us and making everything better for our kids and our pets. We are grateful. We feel safer.”

Planting Community

Sam Tayag, Community Science Program Manager at NHM, says respect for the earth and the microbial communities living on these properties is a parallel objective, one that sets in motion the museum's mission of fostering a thriving, healthy urban ecosystem.

“Community isn't just humans and the folks who were impacted by this. What we’re expecting is that they will see more biodiversity in the soil with less lead.” Tayag hears from participants—whether they are making art, treating the soil, testing, developing the educational materials—that taking action to sequester lead can be psychologically restorative. “We do hear a lot of very personal struggles and people say when they can take action against something that has hurt me in my community, that healing starts taking place. There's a lot of joy in these spaces and a lot of strength. When a community is involved in science, it becomes a healing experience for people, too.”

About Prospering Backyards

Prospering Backyards, an initiative co-created with artists, activists, community scientists and scientists from the Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County (NHMLAC), is helping to address the challenge of lead contamination in L.A. neighborhoods through the power of art, science, and community. NHMLAC is an educational and scientific institution committed to activating its collections and research with the goal of creating and communicating new knowledge about our world. If you believe you have been impacted by lead contamination, you will find resources here.