For centuries the white stork has been ubiquitous with new life. While the folklore of storks delivering babies to homes dates back to ancient Greece and Egyptian mythology, what remains true today is their unique nesting behavior in proximity to humans. This is particularly true in the landlocked country of Armenia, where the white stork is a cultural icon. Specifically, Armenians view the storks as a symbol of prosperity, luck, and fertility.

Understanding and protecting the cultural icon

The preservation and protection of the revered birds is evident through laws that not only protect the birds from hunting, but also protect their nests from being destroyed—which is precarious since they often build their nests on the rooftops of homes.

During nesting season, white storks fly into Armenia from Europe and prefer to build their nests in villages located in close proximity to the Ararat wetlands, where there is plenty of food nearby. They perch their nests on top of homes, electric poles, and even monuments when suitable trees are unavailable. Mating pairs tend to nests that can reach up to five feet in diameter! In some cases the nest can end up blocking water flow from storm drains, causing moisture accumulation in walls and damage to homes. While a nest can be viewed as a costly nuisance to some, many families feel lucky to have stork nests on their homes and install special nest platforms to help preserve the nests without causing any damage.

Unfortunately, infrastructure development plans threaten to drain the Ararat wetlands and jeopardize the habitat these storks need to survive. Community science programs that engage homeowners in supporting habitat conservation and environmental education around the white stork have helped bring awareness to this issue. There are active programs that engage homeowners in helping scientists to identify the stork population in Armenia, measure trends in stork breeding success, and ultimately justify the conservation status of the species.

As these community science programs grow, interest from the Armenian community has soared. Over 1,000 families now participate in programs that report back data electronically through apps or via a hotline to scientists. Village schools now have eco-clubs and festivals that celebrate the storks and teach about the importance of habitat conservation. The nesting season is driving tourism to these villages, with a small number of bird enthusiasts visiting yearly. Even agricultural practices are more cognizant of how DDT pesticide usage affects wetland habitats.

Understanding the effects of DDT was important to scientists in Armenia and Southern California alike, especially in the 1970s when Los Angeles saw a steep decline in the brown pelican population. Dr. Ralph Schreiber, who was a researcher at NHM at the time, was able to identify that DDT was making the eggs thinner and less structurally sound. This discovery led to the ban of DDT in the U.S. and many other countries, and today, we know that DDT also impacted other birds of prey. Through continued research, we are able to understand how humans affect the environment and more importantly, how we can mitigate our impact and create ways for bird eggs and nests to thrive in urban areas.

A bird’s ability to nest on houses and other human structures may also be an important factor in understanding which birds thrive in urban areas. Dr. Allison Shultz, Assistant Curator of Ornithology, and colleagues recently used data gathered by community scientists in L.A. to better understand which, if any, bird traits were associated with birds that prefer to live with humans. “We were surprised by the results,” says Dr. Shultz. “We expected that birds that prefer to live in cities might be more likely to eat a wide variety of foods or be able to live in many different habitats. Instead, we found that it was all about nesting—species of birds that nest on human-built structures were more likely to be found in the city, and species that nest in hollow tree cavities were less likely to be found in a city.” This research shows us that the relationship between bird nests and humans doesn’t just exist in Armenia, but also in the backyards of L.A. residents.

Safe Place for Growing Nestlings

White storks build their nests on top of homes in urban areas, and in the wild storks will nest on cliff sides and trees. Today with habitat degradation, human-made structures provide the height white storks need to protect their young from predators (especially mammals). Like in Armenia, L.A. has plenty of great nesting spaces for many different types of birds! Many of the herons and egrets found in L.A. also nest in trees and large colonies. Ospreys are very well known for nesting on utility poles and today, many sites have installed nesting platforms built specifically for ospreys to help rebound populations affected by DDT in the 1960s and 1970s.

The museum has a history of leveraging the power of research to understand birds in the L.A area and beyond. The story of the storks in Armenia shows us that community scientist observations help scientists to further understand how birds are able to live in cities, and what can be done to help them thrive. This is especially true in Southern California, where local songbirds and robins have a short nesting period of just a few weeks. Dr. Shultz and other musuem researchers hope to continue to use observations made by community scientists to further understand bird behavior—from nest making to egg-laying, and onto the nourishment of young chicks until they are strong enough to fly.

Get involved

Are you interested in sharing your own data on your nest neighbors? Record your observations online to support conservation efforts in your own city by using Nest Watch from The Cornell Lab of Ornithology or share a photo of your own nest neighbors by tagging @nhmla on Instagram and Twitter!

While observing your nest neighbors be sure to not disturb the birds, nests, or objects in the nest so no accidental harm comes to the nestlings.

Check out these photos shared with us by community scientists in L.A.!

Photo courtesy of Amy and Mckenna Rosenberg

This hummingbird nest was built under the eave, on a wind-chime (appropriately designed as a hummingbird), in Long Beach.

Photo courtesy of Rick O’Connor

This mourning dove nestling is on a patio eave in Whittier.

Photo courtesy of Amanda Torres

A hummingbird nest in Huntington Beach teeters on a pinecone strung across a balcony.

Photo courtesy of Cassandra Davis Ramon

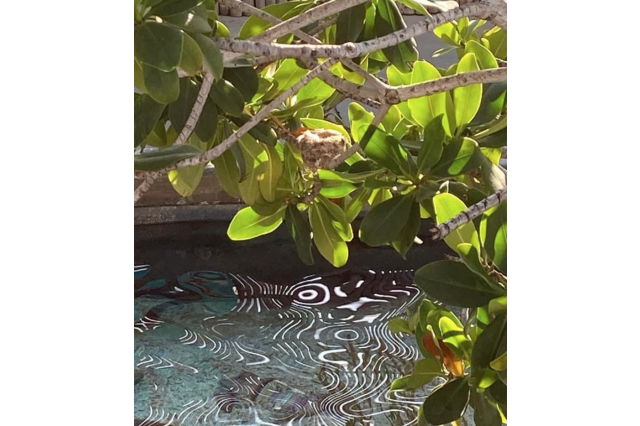

A hummingbird nest precariously perched above the Aquarium of the Pacific’s Shark Lagoon exhibit.

Photo courtesy of Scott Fraser

This Morning Dove (Zenaida macroura) built its nest on a vacant painting pan inside of a home’s garage. Long Beach.

Photo courtesy of Joanna Whitney

A hummingbird nest perched on string lights on a home in Valley Village.

Photo courtesy of Raquel Edpao

A hummingbird with its rosebush-mounted nest in Oxnard.

Photo courtesy of Stan Guerra

Nestling protected within the branches of a caracara orange tree in Northridge.

Photo courtesy of Chantel Cagle

Nest and eggs tucked within a patio eave in San Bernardino.

1 of 1

This hummingbird nest was built under the eave, on a wind-chime (appropriately designed as a hummingbird), in Long Beach.

Photo courtesy of Amy and Mckenna Rosenberg

This mourning dove nestling is on a patio eave in Whittier.

Photo courtesy of Rick O’Connor

A hummingbird nest in Huntington Beach teeters on a pinecone strung across a balcony.

Photo courtesy of Amanda Torres

A hummingbird nest precariously perched above the Aquarium of the Pacific’s Shark Lagoon exhibit.

Photo courtesy of Cassandra Davis Ramon

This Morning Dove (Zenaida macroura) built its nest on a vacant painting pan inside of a home’s garage. Long Beach.

Photo courtesy of Scott Fraser

A hummingbird nest perched on string lights on a home in Valley Village.

Photo courtesy of Joanna Whitney

A hummingbird with its rosebush-mounted nest in Oxnard.

Photo courtesy of Raquel Edpao

Nestling protected within the branches of a caracara orange tree in Northridge.

Photo courtesy of Stan Guerra

Nest and eggs tucked within a patio eave in San Bernardino.

Photo courtesy of Chantel Cagle

A note from the author

During the height of the pandemic, while staying safer-at-home, watching birds fly by my second-story apartment window was one of the few ways I felt safe engaging with nature. Although I live in one of the most polluted and dense neighborhoods in Los Angeles I was able to spot so many amazing birds! It brought me lots of happiness to learn about the incredible urban nature that zooms past me every day. On a particularly special day, I discovered a house sparrow’s nest nestled between a storm drain and my bathroom window. I watched the mother bird gather bugs and twigs for hours. I called my abuelita to share the news, and she told me birds would sometimes nest on her home in Mexico when she was a young girl, and her mother told her it meant we have happy homes. After learning about the Nest Neighbors program in Armenia and the community that was inspired to support conservation efforts that led to the incredible growth of the White Stork population, it felt special to share symbols of good luck from across the world.

Dr. Allison Shultz and Milena Acosta contributed to this article.