Image above by Philippine Consulate General in Los Angeles, Facebook

What we wear makes a difference. Clothing can speak for us, a voice that expresses how we want to present ourselves to the world. A language of its own, clothing tells the story of who you are and the people you may come from or want to be associated with. Historically, the clothes you wore might have been practical for your environment, but often, your clothes also showed that you belonged to a community. As we reach back into our Anthropology collections at the Natural History Museum, we take a long look at articles of clothing in the collection brought to us from across the world. In their travels, some of these pieces have also become a symbol of the people to which they belong.

We can learn a lot from symbols. In an abstract form, they tell us what is important to a person or a group of people. They can take on numerous forms, shapeshifting to tell us stories so they won’t be forgotten. But symbols take shape and evolve over time, creating new interpretations along the way. If a symbol becomes misinterpreted by others, it is important to reflect and ask, what history are we missing? What story isn’t being told?

The salakot is one of those symbols with a story muddled by history and simultaneously sits as a piece of the National Costume of the Philippines. It represented (and still represents) Filipino cultural dress.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

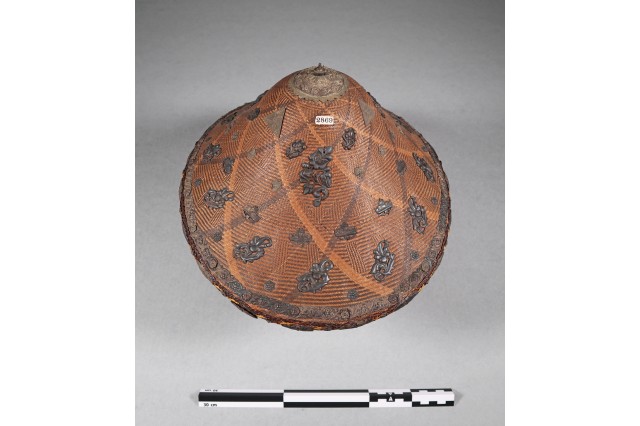

Filipino salakot from Zamboanga, Mindanao and made of palm leaves, bamboo, rattan, paper, and cotton.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of salakot with star pattern at crown

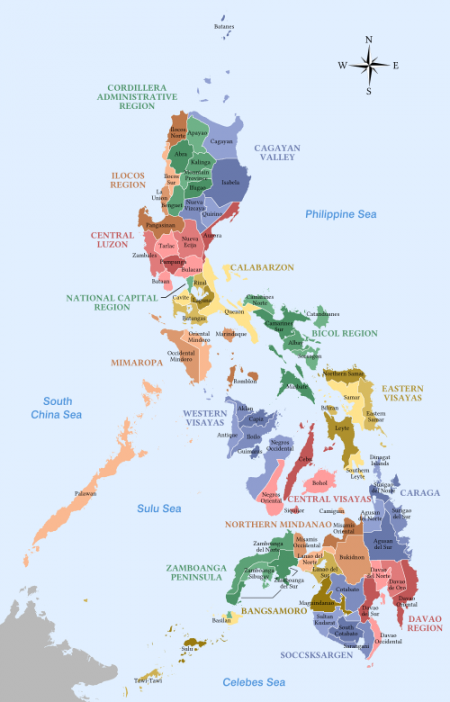

Markytour777, WikiCommons

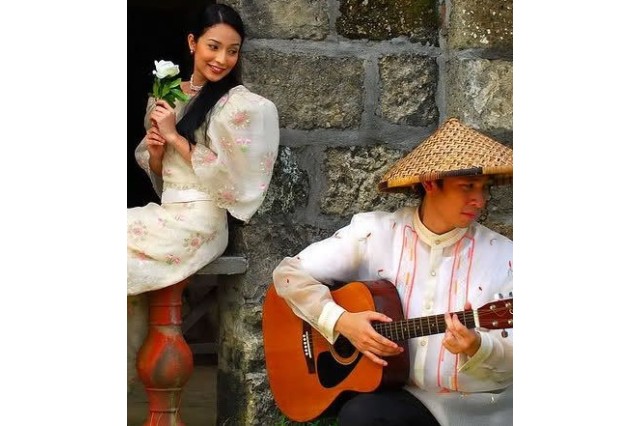

Salakot worn with barong tagalog (embroidered long-sleeved shirt) and baro’t saya (blouse and skirt), part of the National Costume of the Philippines.

1 of 1

Filipino salakot from Zamboanga, Mindanao and made of palm leaves, bamboo, rattan, paper, and cotton.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of salakot with star pattern at crown

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Salakot worn with barong tagalog (embroidered long-sleeved shirt) and baro’t saya (blouse and skirt), part of the National Costume of the Philippines.

Markytour777, WikiCommons

The closest translation of salakot from Tagalog to English is “native hat.” Echoes of the salakot design are seen in European “pith helmets,” no doubt inspired for its usefulness as a firm protective object from the sun or otherwise.

Taking a closer look at the materials the salakot is made from also requires a reflection on the Philippines' natural resources. The Philippines is one of eighteen mega biodiverse countries in the world. The archipelago contains two-thirds of the earth’s biodiversity and is one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots. This unique biodiversity is supported by a wide variety of landscapes and habitats. The Philippines' Indigenous people used the resources from these unique ecosystems to survive and create art and culture within their communities. As of 2016, the number of Indigenous groups in the Philippines is unknown, but there are estimates that Indigenous communities make up about 10 to 20 percent of the population.

Of the many Indigenous communities in the Philippines, the salakot is the headgear is known to be worn by the Tagalog and Kapampangan peoples of the Philippines. Many other helmet variants are found throughout the islands, each interpreted by different ethnic groups in different styles. Most salakot were made from the materials found in the area, including bamboo, palms, and rattan leaves. Some salakots were coated in a resin to make them waterproof and worn as protection from the sun by farmers and fishermen.

The European pith helmet is an adaptation of the Filipino salakot. Pictured here is a Filipino salakot from the Museum’s collection and is shaped similarly to the pith helmet.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Filipino salakot made of palm leaves and embroidered flowers.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of salakot top with embroidered flowers

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Filipino salakot made of palm leaf and rattan strips

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Salakot made of wood with a design of broad black lines and small figures in medallions

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Helmet-shaped salakot made of palm leaves and rattan.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of helmet-shaped salakot made of palm leaves and rattan.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Salakot with tightly woven cords, zig-zag pattern

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Wide-brimmed salakot made of bark, coconut fibers, palms and rattan.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of wide-brimmed salakot made of bark, coconut fibers, palms and rattan.

1 of 1

The European pith helmet is an adaptation of the Filipino salakot. Pictured here is a Filipino salakot from the Museum’s collection and is shaped similarly to the pith helmet.

Filipino salakot made of palm leaves and embroidered flowers.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of salakot top with embroidered flowers

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Filipino salakot made of palm leaf and rattan strips

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Salakot made of wood with a design of broad black lines and small figures in medallions

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Helmet-shaped salakot made of palm leaves and rattan.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of helmet-shaped salakot made of palm leaves and rattan.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Salakot with tightly woven cords, zig-zag pattern

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Wide-brimmed salakot made of bark, coconut fibers, palms and rattan.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of wide-brimmed salakot made of bark, coconut fibers, palms and rattan.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Tassels, feathers, and beads were incorporated into the designs to show wealth and class. The more elaborately designed salakots were handed down, as precious heirloom objects from generation to generation.

In the 19th century, when Spain colonized the Philippines, the salakot design evolved into a symbol of status. Within a Spanish colony, salakot designs begin to incorporate tortoiseshell, precious gems, and even metals like silver. These embellishments became the symbol of the ruling class of the Philippines under Spain’s rule: the principalia. This noble class of Filipinos served as the “go-between” for both the colonizers and the native population as Spain established their pueblos in each neighborhood or “barangay.”

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Filipino salakot with metal ornament inlay

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of Filipino salakot with metal ornament inlay topside

1 of 1

Filipino salakot with metal ornament inlay

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Topside of Filipino salakot with metal ornament inlay topside

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

While the principalia served as an intermediary, this upper class was not seen as equal to the Spanish friars and soldiers stationed in the country. As the Spanish officials continued their systemic abuses against the Indigenous groups, refusing to take off your salakot in front of friars or officials counted as a warrant for arrest or other punishment.

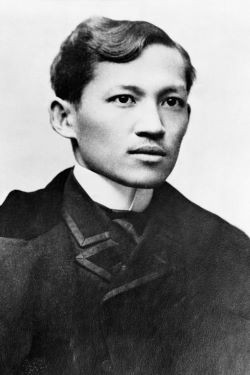

To understand the way in which the salakot symbolism evolved over time and how the salakots were cataloged in museum collections, it is important to provide historical context. In 1872, the Propaganda Movement was started by wealthy and educated upper-class Filipinos, called the Ilustrados. The goal of the movement was to put pressure on Spain to publicize the injustices being carried out in the Philippines and create meaningful reforms where Filipinos had standing equal to any other Spaniard.

One of its primary activists was doctor and writer José Rizal, now considered one of the Philippines’ National Heroes. While Rizal aimed to expose the state of the people under Spanish rule, at the same time a secret anti-colonial political organization, called the Katipunan, began to take root in the Philippines. The Katipunan organized themselves into a revolutionary government and declared a nationwide, armed revolution in August 1896. Months later, the Spanish publicly executed Rizal, accusing him of his role in the revolution for writing his famous book Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not). Rizal’s execution was the catalyst for uniting Filipinos and for two years, provinces in the Philippines would stand against the colonist rule of Spain. The Philippine Revolution ended with the Spanish American War, which was a key moment in the United States setting itself up as a global power.

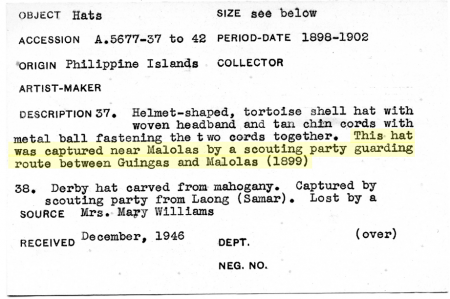

The salakot became the war helmet for both the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine-American War that followed. The Spanish, being defeated by the United States, were set to transfer possession of the Philippines to the United States at the end of the Spanish American War. The Philippine Republic objected to this transfer, and the conflict with the United States was based on the Philippine Republic’s desire for independence. The ensuing Philippine-American War lasted three years, ending in 1902. The Philippines would not have independence from the United States until 1946. In the Museum’s collection, we see some of the salakot described as “captured” by soldiers during an insurrection, which is clearly referring to the Philippine-American War.

The odyssey of this young republic refusing to accept its role as a prized possession of European and American forces shows us a rich story of people struggling with autonomy and gaining independence after 400 years of colonization. Even though the independent country is relatively young, the natural resources of the islands themselves are not. Geologically, the islands are between 10 to 25 million years old. The discovery of an ancient human race dated 50,000 to 67,000 years old was found on the Philippine’s largest island, Luzon. As stated, the biodiversity of the archipelago is astonishing, with about 70 percent of its reptiles and 44 percent of its avian creatures being endemic (meaning found nowhere else in the world) to the islands. As such, we see a wide array of resources used to make salakots including aquatic reptiles like the shell of sea turtles.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Filipino salakot made of tortoiseshell, likely from a hawksbill sea turtle

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

The underside of salakot made of sea turtle shell, likely a hawksbill sea turtle.

1 of 1

Filipino salakot made of tortoiseshell, likely from a hawksbill sea turtle

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

The underside of salakot made of sea turtle shell, likely a hawksbill sea turtle.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

The Philippines hosts natural wonders that have become destinations for anyone wanting to experience a full range of ecosystems found nowhere else; yet these environments are under siege. Large scale tourism, a high rate of population growth due to anti-government sponsored family planning, and a depressed economy all contribute to the destruction of many natural habitats. The very plants and resources that make up the fabrics in the salakot and other National Costumes of the Philippines are in these habitats. Furthermore, Indigenous groups, such as the Ilocano, Igorot, Ifugao, Kalinga, to name a few, reside within some of the most fragile ecosystems.

Many Indigenous peoples within the Philippines are environmental activists today. Indigenous peoples worldwide represent 5 percent of the earth’s human population but protect 80 percent of the earth’s biodiversity; and Indigenous environmental defenders are frequently murdered for their work protecting the lands that are sacred to them. Maybe the salakot, a piece of native dress in the Philippines, will see another transformation as a revolutionary symbol in this decade. Still, there are other ways to learn and to support Indigenous people in the Philippines.

Many activists advocate for Indigenous rights, some bridging the gap between Manila’s high fashion industry and the patterns and textiles created by these groups. Activists cite the responsibility of the wearer of these textiles to know the tribe and the customs of wearing the fabrics. The same is true for the salakot. A useful and practical article of clothing can also have symbolic meaning as we continue to research and understand the context of its history.

A note from the author

Filipino Americans, such as myself, reach to our roots in the Philippines to learn about our family history or cultural history. In the words of Rizal himself, “Those who fail to look back to where they came from, will not reach where they’re going.” A big turning point in my self-education was learning about the archipelago’s Indigenous groups and my connection to them. My family is Ilocano and Kapampangan, my lolo and lola communicated by speaking Tagalog to each other. Both groups are situated on the northernmost island: Luzon. The salakot and headgear’s design is derived from the Kapampangan people, yet the word is Tagalog. My mother speaks three dialects, each one from a different place in Luzon. When I asked her about the salakot, she told me that it was a hat used for sun protection, made out of whatever natural resource was available. To her, it represents Filipino traditions and history. To me, it represents a connection to my pamilya.

Recommended Reading

Noli Me Tangere by Jose Rizal, Harold Augenbraum (Translator)

José Rizal's Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not) has become widely known as the Philippines’ great novel. A passionate love story set against the ugly political backdrop of repression, torture, and murder, "The Noli," as it is called in the Philippines, was the first major artistic manifestation of Asian resistance to European colonialism. Rizal became a guiding conscience—and martyr—for the revolution that would subsequently rise up in the Spanish province.

Brown Skin, White Minds: Filipino - American Postcolonial Psychology

The historical and contemporary reasons for why Filipino -/ Americans display certain attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors - often referred to as colonial mentality - are explored in Brown Skin, White Minds. This book is a peer-reviewed publication that integrates knowledge from multiple scholarly and scientific disciplines to identify the past and current catalysts for such self-denigrating attitudes and behaviors. It takes the reader from indigenous Tao culture, Spanish and American colonialism, colonial mentality or internalized oppression along with its implications on Kapwa, identity, and mental health, to decolonization in the clinical, community, and research settings.